ManyDogs: Big Team Canine Science

CCHIL is elated to be part of a very exciting initiative called the ManyDogs Project that brings together dog behavior and cognition labs worldwide together to study canine science. We have a paper published in Comparative Cognition and Behavior Reviews that introduces this initiative, but here we give a quick summary.

What is the ManyDogs Project?

ManyDogs is a collaboration between dog behavior and cognition labs worldwide interested in running the same studies across sites. It’s an example of big team science, or “collaborations wherein a comparatively large number of researchers pool their intellectual and/or material resources to pursue a common goal”1. There are similar groups that study babies, primates, birds, goats, and fish.

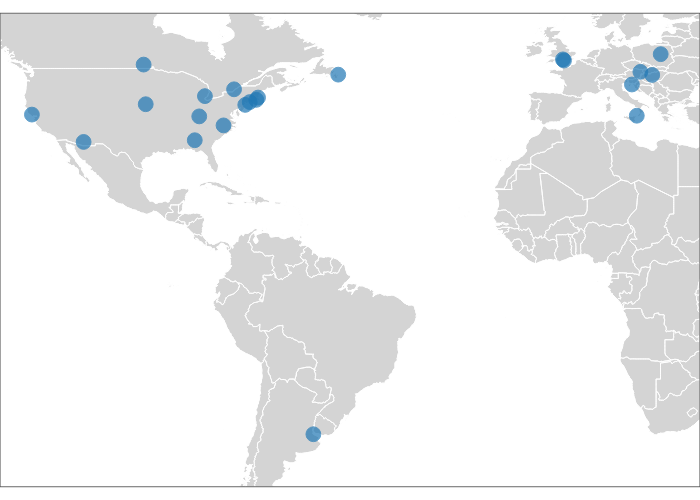

ManyDogs kicked off at a Comparative Cognition Society Conference, where a number of canine researchers got together to talk about joining forces to collect data together. CCHIL was invited to join in March 2020 (yes, that March 2020)—we readily agreed and haven’t looked back since. While starting off with just a handful of labs, we now boast more than 25 participating sites and are intent to keep growing!

What do we do?

Our first order of business was to recruit research sites into our collaboration. This allowed us to build a core group of researchers interested in leading ManyDogs as an organization and growing the research sites to include labs from all over the world. The ManyDogs leadership team works to build our community, maintain our data management infrastructure, and monitor the selection of research projects.

Which leads us to the key function of ManyDogs, which is to organize and support research projects. This involves selecting projects, developing methods, organizing data collection across research sites, analyzing data across sites, publishing scientific papers, and archiving materials and data from projects.

Our first project (ManyDogs 1) was completed and published in 2023. It focused on how dogs follow human point gestures2. We have survey data from over 700 dogs and behavioral data from over 450 dogs. I’d say that was a success!

Why is it important?

Many areas of behavioral science are facing a reckoning about how we do research. As scientists, we want our work to be high quality in a number of ways:

- rigor—using strong methods that test what we want to test

- reproducibility—ensuring that our methods and analyses can be reproduced by other scientists

- replicability—ensuring that our findings can be replicated by other scientists

- robustness—ensuring that our findings are generalizable across a wide range of contexts

Rigor

If you talk with ten scientists, you’ll hear ten different opinions on how to run a study. ManyDog’s big team science approach takes advantage of this by having many scientists come together to develop research designs and methods. Using the collective wisdom of lots of smart people helps ensure the rigor of the methods used in the studies.

Reproducibility

For far too long, the descriptions of methods in scientific papers were too sparse, and important information such as the experimental materials, data, and analysis records were not published along with the scientific article. The open science movement has changed that by encouraging researchers to write thorough methods descriptions and post experimental materials, data, and analysis records with scientific publication or on separate (but linked) repositories such as the Open Science Framework. At ManyDogs, we embrace open science and try to ensure that our work is as reproducible as possible, so other scientists can take our materials and data and check our work…or expand on it.

Replicability

To achieve replicable science, one of the best things that we can do is use large sample sizes to include all of the variability that we see in subjects. A small sample size can result in an unrepresentative sample that biases findings. Behavioral testing in dogs is time consuming, and typical sample sizes for behavioral studies often range from 20-50 dogs. Combining forces across labs allows us to test many more dogs than individual labs can. Collecting data on hundreds of dogs increases the chances that our findings are consistent and replicable.

Robustness

Collecting data in one lab from one population may not carry over into other locations and populations. Different labs have different procedures for how they do things. And sometimes those procedures might have unintended effects on findings. For instance, the gender of the experimenter can effect behavior and stress responses in rodent studies3, so a different gender composition across labs could influence results. One way to increase robustness of findings across labs and populations is to include lots of labs and populations all in the same study! That’s built into the big team science approach of collecting data across many research sites. So hopefully our findings are robust to population differences.

Unique research questions

In addition to the many methodological benefits of big team science, there is one super important advantage to ManyDogs—we can ask unique research questions that we simply cannot address easily in individual labs. Any time we talk about dog behavior, the first question people ask is “Are there breed difference?”. This question is extremely difficult for a single lab to answer (at least for behavioral questions) because there are hundreds of breeds and most sample sizes are in the low dozens. So there’s often no way to directly address breed differences in single lab studies of behavior. But with ManyDogs, we have hundreds of dogs and can start to explore some questions about breed differences (though really thousands of dogs may be needed to get at breed effects well).

Another unique question that ManyDogs can address that is hard to address for individual labs is the effect of culture on dog behavior and cognition. Dogs are treated differently across and within countries. How owners treat their dogs could have direct effects on their behavior. Therefore, dogs living in different cultures could behave differently. We can directly test potential cultural differences in dog behavior by comparing data across labs in different countries—a bonus benefit of the international reach of ManyDogs.

What’s next?

Since ManyDogs 1 is complete, we have moved on to ManyDogs 2, which will focus on overimitation4. ManyDogs 2 is currently in the methods development phase with data collection probably starting in 2025.

Another project that we’re super excited about is a big-big team science project. We mentioned before that there are other projects similar to ManyDogs that focus on babies, primates, birds, goats, and fish. Well, all of the groups (and more) have joined together in a ManyManys project that will collaborate across all of the labs in all of these projects. We will be testing dozens of species! ManyManys 1 will focus on reversal learning5 and is in the methods development phase.

ManyDogs and the other big team science projects are not meant to replace studies in individual labs. But they can offer unique opportunities to answer important questions with large sample sizes. For ManyDogs, this includes questions about dog behavior at a scale that is simply not feasible for most individual labs. We’re excited about the future of ManyDogs and canine behavioral science!

Reference

ManyDogs Project, Alberghina, D., Bray, E., Buchsbaum, D., Byosiere, S.-E., Espinosa, J., Gnanadesikan, G., Guran, C.-N.A., Hare, E., Horschler, D., Huber, L., Kuhlmeier, V.A., MacLean, E., Pelgrim, M.H., Perez, B., Ravid-Schurr, D., Rothkoff, L., Sexton, C., Silver, Z., & Stevens, J.R. (2023). ManyDogs Project: A big team science approach to investigating canine behavior and cognition. Comparative Cognition and Behavior Reviews, 18, 59-77.

News article: To the dogs: Stevens co-directing global consortium on canine research by Scott Schrage, UNL University Communications.

Updated 2024-05-14 to include alt text for images.

Footnotes

Baumgartner, H. A., Alessandroni, N., Byers-Heinlein, K., Frank, M. C., Hamlin, J. K., Soderstrom, M., Voelkel, J. G., Willer, R., Yuen, F., & Coles, N. A. (2023). How to build up big team science: A practical guide for large-scale collaborations. Royal Society Open Science, 10(6), 230235.↩︎

ManyDogs Project, Espinosa, J., Stevens, J.R., Alberghina, D., Alway, H.E.E., Barela, J.D., Bogese, M., Bray, E.E., Buchsbaum, D. Byosiere, S.-E., Byrne, M., Cavalli, C. M., Chaudoir, L. M., Collins-Pisano, C., DeBoer, H.J., Douglas L.E.L.C., Dror, S., Dzik, M.V., Ferguson, B., Fisher, L., Fitzpatrick, H.C., Freeman, M.S., Frinton, S.N., Glover, M.K., Gnanadesikan, G.E., Goacher, J.E.P., Golańska, M., Guran, C.-N.A., Hare, E., Hare, B. Hickey, M., Horschler, D.J., Huber, L., Jim, H.-L., Johnston, A.M., Kaminski, J. Kelly, D.M., Kuhlmeier, V.A., Lassiter, L., Lazarowski, L., Leighton-Birch, J., MacLean, E.L., Maliszewska, K., Marra, V., Montgomery, L.I., Murray, M.S., Nelson, E.K., Ostojić, L., Palermo, S.G., Parks Russell, A.E., Pelgrim, M.H., Pellowe, S.D., Reinholz, A., Rial, L.A., Richards, E.M., Ross, M.A., Rothkoff, L.G., Salomons, H., Sanger, J.K., Santos, L., Shirle, A.R., Shearer, S.J., Silver, Z.A., Silverman, J.M., Sommese, A., Srdoc, T., St. John-Mosse, H., Vega, A.C., Vékony, K., Völter, C.J., Walsh C.J., Worth, Y.A., Zipperling, L.M.I., Żołędziewska, B., & Zylberfuden, S.G. (2023). ManyDogs 1: A multi-lab replication study of dogs’ pointing comprehension. Animal Behavior & Cognition, 10(3), 232-28.↩︎

Georgiou, P., Zanos, P., Mou, T.-C. M., An, X., Gerhard, D. M., Dryanovski, D. I., Potter, L. E., Highland, J. N., Jenne, C. E., Stewart, B. W., Pultorak, K. J., Yuan, P., Powels, C. F., Lovett, J., Pereira, E. F. R., Clark, S. M., Tonelli, L. H., Moaddel, R., Zarate, C. A., … Gould, T. D. (2022). Experimenters’ sex modulates mouse behaviors and neural responses to ketamine via corticotropin releasing factor. Nature Neuroscience, 25(9), 1191–1200.↩︎

Overimitation is the persistent imitation of unnecessary actions. Lyons, D. E., Young, A. G., & Keil, F. C. (2007). The hidden structure of overimitation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(50), 19751–19756.↩︎

Reversal learning involves training animals on one association (e.g., pressing red button yields reinforcer but pressing green does not). After the animals acquire this association by reliably choosing the reinforced option, the contingencies switch (e.g., now green is reinforced but red isn’t). The question is how long does it take to learn the newly reversed contingency. Researchers may continue to reverse the learning contingencies to see if the animals catch on. Thus, reversal learning is a measure of behavioral flexibility. Yaple, Z. A., & Yu, R. (2019). Fractionating adaptive learning: A meta-analysis of the reversal learning paradigm. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 102, 85–94.↩︎